For all you Shackleton Fans (and everyone else also) the Saga of Sir Earnest Shackleton and the 27 members of his crew on their 1914 “Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition” attempt to cross the Antarctic Continent is one of the greatest (and most thrilling) perseverance and survival stories from the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration”, or, in my opinion, “ever”, in the history of exploration, anywhere.

The Boss

Shackleton, affectionately known as The Boss by his crew, was an Irish Explorer, very familiar with Antarctica; he had made two attempts to reach the then-unreached South Pole; once with Scott and once on his own expedition; the Nimrod Expedition (aka British Antarctic expedition) 1907-1909, where he and three companion’s got within 112 miles of the pole; the furthest south at that time, but had to retreat because of difficult and life-threatening conditions..

After Amundsen became the first to reach the pole on 14 December 1911, followed by Scott on 17 January 1912, Shackleton turned his energies to organizing the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Shackleton’s family motto was “By Endurance we Conquer”.

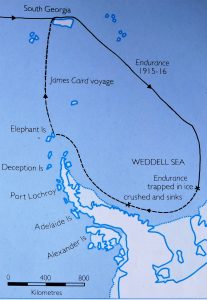

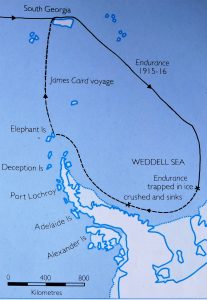

The (very) short version of this 21 month epic is that the Endurance (the name that Shackleton gave the ship) set out from the Grytviken Whaling Station on South Georgia Island on 5 December 1914 (Austral Summer), battling ever increasing (and unusually severe) ice.

Whaling Boat – Harpoon Cannon on the Bow – Crow’s Nest (for spotting their quarry) on the mast

By 24 January 1915 the Endurance was totally trapped in the pack ice, and was slowly swept northward.

The situation became progressively worse.

At that point they had ample supplies (as they had planned the Antarctic crossing), but by 24 February they set up a camp on the ice (though they still had access to the ship).

In May the sun set for the Austral Winter, and conditions continued to deteriorate.

By 24 October the three lifeboats and the last remaining supplies were taken off the Endurance, and the ship was totally abandoned and it was crushed and sank on 21 November 1915, almost 1 year since they had left South Georgia.

The entire crew remained camped on the ice until it broke up, making that no longer possible, and on 9 April they took to the three lifeboats and headed for the only realistic land fall; Elephant Island; a remote and inhospitable speck of land, rarely visited by whaling ships, let alone anyone else.

They made an initial landfall at a miserable location on 14 April, and moved on the next day to a slightly less terrible location, which they named Camp Wild (Frank Wild had been with Shackleton on all of “The Boss’” expeditions, and was his right hand man and alter ego).

Camp Wild is the little rocky strip in the center of the picture.

Their only source of food were penguins and seals.

Their only shelter from April 15, 1916 until August 30, 1916 were the two remaining lifeboats, turned upside down on a rock wall,

with 5 foot inside headroom and very limited cover on the sides.

Camp Wild again – the small rocky strip to the left of the triangle.

Shackleton ordered one of the open lifeboats strengthened, decked over, and made as seaworthy as possible (the 22 Foot James Caird), and on 24 April The Boss with a crew of five set sail across the Southern Ocean for the speck of South Georgia Island, 800 miles away.

Replica of the James Caird in the Grytviken Museum

On May 10th, after a daunting and “adventure filled” journey they made land fall at South Georgia; unfortunately, on the opposite side of the island from the whaling stations.

The only way to reach the stations (and final rescue) was to cross the uncharted island, which Shackleton and two companions did in a single push over glaciers on the 19th and 20th.

None of then had any mountaineering experience – they took wood screws from the James Caird and put them through their boots (sharp side down, of course) to gain traction on the glaciers they had to cross, at elevations up to 3,000 feet. They covered 36 miles in 39 hours; a speed that has not been equaled by professional mountaineers later in the 20th century (reverenced in the film, linked below). A truly remarkable accomplishment, and a testament to Perseverance and Endurance, to save their own lives and the other 25 members of the crew.

On the 21st a ship was dispatched to rescue the three remaining members of the James Caird (who had been physically unable to attempt the crossing of South Georgia), and on the 22nd of May the first (of four) attempts to rescue the remaining 22 men at Camp Wild was launched.

The first three attempts were frustrated by pack ice – they didn’t even get close enough to Camp Wild to say “hang on, guy’s – we made it to South Georgia, and we’re going to get you – keep your spirits up – you WILL be rescued”.

However, it wasn’t until 30 August 1916 (more than 4 months later) that a ship provided by the Chilean Government (with Shackleton on board) reached Camp Wild to rescue the rest of the crew.

The entire expedition lasted 21 months; not a single life was lost from the crew of the Endurance; Shackleton; “The Boss” was enshrined as one of the most successful expedition leaders, ever, and all returned home (many to fight in the closing months of the First World War, and some died in the conflict).

Shackleton was still lured by the Antarctic, and in 1921 launched yet another expedition with the goal to circumnavigate the Antarctic Continent.

However, on January 25, 1922 “The Boss” died in his cabin on the ship, in Grytviken, and is buried in the Whaler’s / Seaman cemetery there.

On our 2018 Antarctic Adventure we visited Grytviken; the Boss’ grave and the whaling station & museum where there is a replica of the James Caird.

We all drank the traditional toast of Scotch (his favorite, even though he was Irish) – half for us and half cast upon the Boss’ resting place.

Frank Wild, the Boss’ right hand man, who lived a much longer life, is (amusingly, to me anyhow) buried on the Boss’ left side (looking down from the Boss’ headstone) or right side looking up; just to my right – picky, picky.

The Museum

On the day following our Grytviken visit we went to Fortuna Bay, and “fortunately” (pun intended), conditions were sufficiently wave-free that were able to land safely and hike up just over 1,000 feet and intersect the path where “The Boss” and his two companions first heard the 7AM come-to-work whistle for the workers at the Stromness Whaling Station, so they then knew that they had “made it” and that rescue was at hand.

Fortuna Bay – we climbed up on a path on the rocks to the left of the glacier

The view from the top – Stromness Station barely discernible at the bottom, just to the left of the rock ridge

“Explorer George” at the top of the pass, above the waterfall and Stromness

We followed Shackleton’s path down, past the waterfall that they had to descend (steep and frozen) to the (now abandoned) station, where we were “rescued” by our Zodiacs.

Stromness

An incredibly memorable and emotional experience for me; to have walked in the Boss’ footsteps.

For those of you wishing additional information:

An excellent 40 Minute film, the story of Shackleton Scotch and an expedition which TODAY February 10, 2019 is in the Weddell Sea and searching the location of the sinking of the Endurance, attempting to locate the wreckage, and last (but by no means least), a wonderful article that my friend Kraig Becker did about The Boss and his (Kraig’s) visit to South Georgia, which appeared in Popular Mechanics on June 17, 2017.

Film

Shackleton Whiskey

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=shackleton+whiskey+story

The current Expedition to find the Endurance

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-47192952

Kraig Becker’s Article

Chasing Ernest: A Journey to South Georgia to Find the Ghost of Shackleton

https://www.popularmechanics.com/adventure/outdoors/a26938/south-georgia-island-ernest-shackleton/

Thanks a lot, Dave. Glad you enjoyed it. A second pair of eyes is always helpful. I think I got the centuries straight, now.

Those photos bring back lots of memories. South Georgia is definitely a special place, whether you’re a Shackleton fan or not. Glad you enjoyed it as much as I did.

Thanks, Kraig. It was fun reliving it when we were together in Denver, and fun putting the post together. I’ve shared your article with a number of my friends, and just added it to the post

Thanks, Kraig, for the article in Popular Mechanics. And thanks, George, for the blog. What a great trip! Kraig, I suggest you reach out to Kira Sadler (Kira@voicesforbiodiversity.org) to see if she’d like to re-post a link to your article about Shakleton on VoicesforBiodiversity.org’s (V4B’s) social media pages. I’m the founder of V4B, which shares stories from around the globe, usually about nature and biodiversity, in an effort to protect the environment. You can check out our website: voicesforbiodiversity.org. Kira is the managing editor.

Thanks Tara! I’ll be sure to drop Kira a note when I get the chance. Glad you enjoyed my own little piece on the Shackleton story.

Thanks, Cristy, for following along, and for your friendship and support

Great blog post, great photos, good summary of the Shackleton expedition. Thanks very much.

Glad you enjoyed it, Yale. Nice lunch today. Cheers

Thanks for this. I’m a member of the Explorers Club, and Tim and Alexandra made a wonderful presentation on the successful, magnificent, re-creation of her grandfather’s voyage, which I had the pleasure of attending in March 2016. It was a magnificent achievement. Tim wrote a book, and there’s an excellent film as well. Thanks for expanding my brief story.